Angel Of Death

Within the walls of Warren Correctional Institution in Lebanon, Ohio, Donald Harvey, inmate number A-199449, a self-professed angel of death, is serving out four consecutive life sentences. From April 1983 to September 1986, while working as an orderly for Drake Memorial Hospital in Cincinnati, Ohio, Harvey committed a series of murders. It has been nearly 15 years since Harvey's arrest and conviction, many questions still remain: why had such a seemingly bright and ambitious man taken it upon himself to play God with the lives of so many? Were these truly mercy killings, as he claimed , or were they nothing more than an outlet for a twisted man to achieve a sick form of gratification?

Donald Harvey was born in Butler County, Ohio, in 1952.

Shortly after his birth, Harvey's parents relocated to Booneville, Kentucky, a small community nestled away on the eastern slopes of the Appalachian Mountains. In an August 14, 1987, interview with Cincinnati Post reporter Nadine Louthan, Harvey's mother, Goldie Harvey, recalled that her son was brought up in a loving family environment.

"My son has always been a good boy," she said.

Martha D. Turner, who was principal of the elementary school Harvey attended for eight years, backed up McKinney's comments in her own interview with the Cincinnati Post:

"Donnie was a very special child to me," she said. He was always clean and well dressed with his hair trimmed. He was a happy child, very sociable and well-liked by the other children. He was a handsome boy with big brown eyes and dark curly hair he always had a smile for me. There was never any indication of any abnormality."

Former classmates of Harvey described him as a loner and teacher's pet. He rarely participated in extracurricular activities, opting instead to read books and dream about the future. Following his graduation from Sturgeon Elementary School, Harvey entered Booneville High School in 1968. Earning A's and B's in most classes with little effort, he became bored with the daily routine and dropped out. Having no real goals, Harvey was not sure what he wanted to do with his newfound freedom. For unknown reasons he eventually decided to relocate to Cincinnati, Ohio, where he secured a job at a local factory.

In 1970 work began to slow at the plant and Harvey was eventually laid off. His mother called him a few days later and asked him to travel to Kentucky and visit his ailing grandfather, who was recently placed in a hospital there. Harvey agreed and within days set off for Marymount Hospital in London, Kentucky. Although no one knew it at the time, this trip would later prove to be the beginning of a long journey into madness and murder.

While in Kentucky, Harvey spent much of his time at Marymount Hospital, and was soon well known and liked by the nuns who worked there. During one particular conversation, one of the nuns asked Harvey if he would be interested in working there as an orderly. Since he was currently unemployed and didn't want another factory job, Harvey agreed and started work the next day. Although he was not a trained nurse or doctor, Harvey's duties required him to spend hours alone with patients. Some of his duties included changing bedpans, inserting catheters and passing out medications.

Harvey's first few weeks at the hospital were uneventful, but something snapped within him along the way. To this day criminal psychologists are unable to explain what brought out his murderous tendencies. Whether he was unable to cope with the pain and suffering around him or simply enjoyed watching his victims die may never be known. According to Harvey's later confessions, he considered himself an "angel of death," or mercy killer. But the details he eventually revealed about his first murder negate that self-serving description.

During an evening shift, just months after starting at the hospital, Donald Harvey committed his first murder. Years later, in a 1997 interview with Cincinnati Post reporter Dan Horn, Harvey described it: When he walked into a private room to check on a stroke victim, the patient rubbed feces in his face. Harvey became angry and lost all control.

"The next thing I knew, I'd smothered him," he said. "It was like it was the last straw. I just lost it. I went in to help the man and he wants to rub that in my face."

Following the murder, Harvey cleaned up the patient and hopped into the shower before notifying the nurses.

"No one ever questioned it," he said.

Just three weeks after committing his first murder, he killed again when he disconnected an oxygen tank at an elderly woman's bedside. As the weeks went by and no one detected foul play in his first two murders, Harvey became more brazen. Whether out of boredom, opportunity or experimentation, his methods varied with each murder. He used various items, such as plastic bags, morphine and a variety of drugs, to kill more than a dozen patients in a year. In one case, he chose an exceptionally brutal method. The patient had an argument with Harvey because he thought Harvey was trying to kill him, and during the course of that argument, he reportedly knocked Harvey out with a bedpan. Upon recovering from the blow, Harvey waited till later that night, snuck into the patient's room, and stuck a coat hanger through his catheter. As a result of the puncture, infection set in and the man died a few days later.

On March 31, 1971, a drunk and disorderly Harvey was arrested for burglary. While being questioned about the crime, Harvey began babbling incoherently about the murders he had committed. The arresting officers looked into his claims and questioned him extensively about them, but in the end they were unable to find any substantial evidence to back them up, or charge him with any crime relating to them. A few weeks later he went to trial for the burglary charges and pleaded guilty to a reduced charge of petty theft. After paying a small fine for his indiscretion, Harvey decided it was time for another change of scenery and enlisted in the United States Air Force.

Harvey served less than a year in the Air Force before he received a general discharge in March 1972. His records list unspecified grounds for the discharge, but it was widely rumored at the time that his superiors had learned of his confessions to the Kentucky police and did not want to deal with any similar matters in the future. After his release from the military, Harvey dealt with several bouts of depression. By July 1972, he was unable to control his inner demons and decided to commit himself to the Veteran's Administration Medical Center in Lexington, Kentucky.

Harvey remained in the mental ward of the facility until August 25, but then admitted himself again a few weeks later. Following a bungled suicide attempt in the hospital, Harvey was placed in restraints and over the course of the next few weeks received 21 electroshock therapy treatments. On October 17, 1972, Harvey was again released from the hospital. Goldie Harvey later condemned the hospital for releasing her son so abruptly, feeling that he had shown no apparent signs of improvement from the time of his admittance.

Harvey spent the next few months trying to get his life back in order and eventually found work as a part-time nurses' aide at Cardinal Hill Hospital in Lexington. In June 1973, he started a second nursing job at Lexington's Good Samaritan Hospital. Harvey kept both jobs until August 1974, when he took up a job as a telephone operator, and then secured a clerical job at St. Luke's Hospital in Fort Thomas, Kentucky. According to his later confessions, Harvey was able to control his urge to kill during this time. The more feasible explanation would be that he did not have the same access to the patients as he did at Marymount Hospital, which could also explain why he shifted from job to job during this time.

The majority of serial killers are opportunists, and Donald Harvey was a man with few opportunities. He had not yet evolved enough to take his urges outside of the place he felt safe in committing his crimes -- the dimly lit patient rooms -- his killing sanctuaries. Harvey was a different kind of hunter and in order for him to get hold of his prey, he had to first find the right environment.

In September 1975, Harvey moved back to Cincinnati, Ohio. Within weeks he got a job working night shift at the Cincinnati V.A. Medical Hospital. Harvey's duties varied and he performed several different tasks, depending on where he was needed at the time. He worked as a nursing assistant, housekeeping aide, cardiac-catheterization technician and autopsy assistant. Harvey had found his niche and wasted little time in starting where he had left off. Since he worked at night, he had very little supervision and unlimited access to virtually all areas of the hospital.

Over the next 10 years, Harvey murdered at least 15 patients while working at the hospital. He kept a precise diary of his crimes and took notes on each victim, detailing how he murdered them -- pressing a plastic bag and wet towel over the mouth and nose; sprinkling rat poison in a patient's dessert; adding arsenic and cyanide to orange juice; injecting cyanide into an intravenous tube; injecting cyanide into a patient's buttocks. All the while Harvey was committing his crimes, he was refining his techniques by studying medical journals for underlying hints on how to conceal his crimes.

Over the years, he amassed an astounding 30 pounds of cyanide, which he had slowly pilfered from the hospital and kept at home for safekeeping. Typically, Harvey would mix a vial of cyanide or arsenic at home and then bring it to work. When no one was around, he would slip the mixture into his victim's food, or pour it directly into their gastric tube.

The early 1980's brought about variations in Harvey's methods. He moved in with a gay lover, Carl Hoeweler, and soon began poisoning him out of fear that his mate was cheating on him. Harvey would slip small doses of arsenic into Hoeweler's food so that he would be too ill to leave their apartment. Harvey's confidence was hitting peak levels and he began feeling as though he was unstoppable. On one occasion, following an argument with a female neighbor, Harvey laced one of her beverages with hepatitis serum, nearly killing her before the infection was diagnosed and treated. Another neighbor, Helen Metzger, was not so lucky. Harvey put arsenic in one of her pies, and she died later that week at a local hospital.

In April 1983, Harvey had a squabble with Hoeweler's parents and began to poison their food with arsenic. On May 1, 1983, Hoeweler's father, Henry, suffered a stroke and was remitted to Providence Hospital. Harvey visited Henry Hoeweler there and placed arsenic in his pudding before leaving. Hoeweler died later that night. Harvey continued to poison Carl's mother, Margaret, off and on for the next year, but was unsuccessful in his attempts to kill her. In January 1984, Hoeweler broke off the relationship with Harvey and asked him to move out. Harvey was angry at the rejection and spent the next two years trying to kill Hoeweler with his poisonous concoctions. At one point he even tried to kill a female friend of Hoeweler as a way to get his revenge. While neither attempt worked, he did manage to land Hoeweler in the hospital at one point, as a result of the poisons he had unknowingly ingested.

While leaving work on July 18, 1985, security guards noticed Harvey acting suspiciously and decided to search a gym bag he was carrying with him. Inside the satchel, the guards discovered a .38-caliber pistol, hypodermic needles, surgical scissors and gloves, a cocaine spoon, various medical texts, two occult books, and a biography of serial killer Charles Sobhraj. Fined $50.00 for carrying a firearm on federal property, Harvey was then given the option to quietly resign from his job rather than being fired. Nothing about the incident was ever noted in his work record and hospital authorities did not open an investigation to determine if Harvey had committed any other crimes while working at the hospital.

Seven months later, in February 1986, Harvey once again got work at a local hospital. This time he was hired as a part-time nurses' aide at Cincinnati's Drake Memorial Hospital. His new employers were unaware of the incident at his previous job, and his work folder said nothing but good things about him. Harvey soon earned a full time position at the hospital and settled back into his old routine. Over the next 13 months, Harvey murdered another 23 patients, by disconnecting life support machines, injecting air into veins, suffocation and injections of arsenic, cyanide and petroleum-based cleansers.

Authorities became suspicious of Harvey in April 1997, after the death of John Powell, a patient who was comatose for several months, but had since started to recover. During the autopsy, an assistant coroner noticed the faint sent of almonds, the tell tale sign of cyanide. Authorities were unable to find any evidence or motive pointing toward any of Powell's friends or family members, so they soon began to focus on hospital employees, whom had access to Powell's room. The list was short, and upon learning Donald Harvey's hospital nickname, "Angel of Death," given to him because he always seemed to be around when someone died, authorities began to focus their entire investigation on him.

In April 1987, after securing a search warrant for Harvey's apartment, investigators found a mountain of evidence against him: jars of cyanide and arsenic, books on the occult and poisons, and a detailed account of the murder, which he had written in a diary. Following this new discovery of evidence, Harvey was arrested on one count of aggravated murder, and after filing a plea of not guilty by reason of insanity was held under a $200,000 bond. The evidence against Harvey was growing rapidly, and investigators were beginning to look into several other mysterious deaths at the hospital. Harvey realized that it was only a matter of time before they discovered the full extent of his crimes, and decided he should try to make a plea bargain to avoid Ohio's death penalty.

On August 11, 1987, 35-year-old Harvey sat down with investigators and confessed to committing 33 murders over the past 17 years. As the days went by, that number eventually grew to 70 in all. Investigators were skeptical of the numbers Harvey was giving them, and wanted to have his mental state assessed prior to taking his claims as fact. Following several psychiatric tests by numerous experts, a spokesman for the Cincinnati prosecutor's office explained the dilemma to the Cincinnati Post:

"This man is sane, competent, but is a compulsive killer," he said. "He builds up tension in his body, so he kills people."

Donald Harvey entered the courtroom on August 18, 1987, and pled guilty to 24 counts of aggravated murder, four counts of attempted murder, and one count of felonious assault. Just four days later, a 25th guilty plea earned him a total of four consecutive 20-years-to-life sentences. In addition to his life terms, Harvey was fined $270,000.

Harvey was indicted in Kentucky on September 7, 1987, where he confessed to committing 12 murders while employed at Marymount Hospital. In November, he pleaded guilty and was sentenced to eight life terms plus 20 years. In February 1988, he entered guilty pleas on three additional Cincinnati homicides and three attempted murders, drawing three life sentences plus three terms of seven to 25 years. Two years later, the investigation into the remaining deaths was closed after investigators determined that there was not enough evidence to pursue them.

In a 1991 interview with a reporter from the Columbus Dispatch, Harvey gave a rare glimpse into his mindset:

"Why did you kill?"

"Well, people controlled me for 18 years, and then I controlled my own destiny. I controlled other people's lives, whether they lived or died. I had that power to control."

"What right did you have to decide that?"

"After I didn't get caught for the first 15, I thought it was my right. I appointed myself judge, prosecutor and jury. So I played God."

On July 23, 2001, the Associated Press printed an article listing the worst serial killers in the United States. Donald Harvey was rated number one, followed by John Wayne Gacy, Patrick Kearney, Bruce Davis and Dean Corll.

Donald Harvey's first scheduled parole hearing is set for 2047. He will be 95.

One would think that cases such as Harvey's and Shipman's would galvanize the medical community worldwide to develop procedures to safeguard against murder in medical institutions. However, discoveries of serial murders within hospitals have risen drastically over the years. The number of victims these serial killers are able to claim before attracting attention strains credibility. British Dr. Harold Shipman is one of the world's most prolific serial killers, claiming at least 215 victims. The list of medics who kill and their number of victims continues to grow:

Richard Angelo, Long Island, New York, at least 10 murders

Orville Lynn Majors, Clinton, Indiana, at least 130 murders

Roberto Diaz, Riverside, California, 12 murders

Brian Rosenfeld, Florida, 23 possible murders

Michael Swango, New York, at least 4 murders

Efren Saldivar, California, at least 6 murders

Beverley Allitt, Britain, at least 4 murders

Genene Jones, Texas, at least 20 murders

Jane Toppan, Massachusetts, at least 31 murders

Waltraud Wagner, Maria Gruber, Ilene Leidolf and Stephanija Mayer, all from Vienna, at least 15 murders

The above list is far from inclusive and does not address the hundreds of suspicious deaths of patients in hospitals and nursing homes. Until hospital employees are screened effectively, staff members are trained to be more vigilant , hospital administrations are more receptive to investigating suspicious cases at an early stage and stricter regulations are put in place, these crimes will continue to plague justice systems around the world.

Well-known forensic scientist Henry Lee summed it up quite well in an April 29, 2002, interview he gave to the Los Angeles Times, regarding Efren Saldivar and similar crimes. He said murders committed by hospital staff were the easiest kind of serial killing to get away with.

"You have to figure out who the victims were long after they were buried," he said. "You have to dig up [bodies]. You are going to have a difficult time finding true trace drug or elements in there. The next issue is how to link to the suspect. Why him? What's the proof? Prepare to fail."

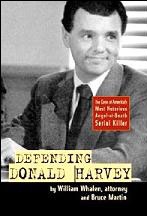

The odd thing about William Whalen's new book describing his relationship with killer nurse Donald Harvey is that while he's ambivalent about the way Harvey has long fed on publicity, he's also giving him this chance to "tell his story." Actually, Defending Donald Harvey (Emmis Books) is largely Whalen's story. He was Harvey's defense attorney, and one might easily question the ethics of some of his decisions. For example, after the first murder came to light, he urged a suspicious reporter to "keep digging" and decided that since Harvey had confessed to him a number of hospital murders, he needed to protect society rather than attempt to get his client off. He justifies that, hoping to get readers to sympathize with his difficult position, and many will. Nevertheless, there are several situations throughout this case in which Whalen seems less concerned with the demands of our justice system than with his personal issues. And, surprisingly, he remained friends with Harvey after his part was done. It's difficult to know, when all is said and done, what he really thinks about Harvey: Sometimes this serial killer is a monster, sometimes merely a pathetic human being.

The story is familiar to anyone who knows about healthcare serial killers, so there's not much new here. Even the reporter, Pat Minarcin, who broke the story and who adds an "Afterword," merely repeats most of what Whalen says. Since there has been no other book on Harvey, this is a good addition to the extant literature on serial killers, but otherwise there seems little justification for retelling Harvey's story at this time.

Harvey was caught when an autopsy revealed a toxin in the body of a male patient, John Powell, and at the time, no one put much effort into considering that he may have caused other deaths as well. It was Harvey himself who started the momentum by confessing to his public defender, who then urged Minarcin to find a way to dig up evidence. Harvey told Whalen that he had lost count of how many people he'd killed (including people outside the hospital), but that it had not been more then seventy. In the end, says Whalen, he was convicted of thirty-six murders and one charge of manslaughter, although beyond the official tally there were clearly many more victims.

Harvey continues to insist that he was a mercy-killer, but the facts indicate otherwise. Over the course of eighteen years in several different institutions, he killed for petty reasons as well as mercy. One man he just didn't like; another he killed out of revenge. And then there were the acquaintances he poisoned with arsenic who just happened to have annoyed him. There seems little doubt that he was engaged in occult practices when he chose some of his victims, and the opening scene of this book has him lighting candles that stand for specific people and deciding from a candle's flicker that the person symbolized by that candle should die. He supposedly believed he was receiving commands from some spirit named Duncan. Even so, Whalen wants to accept the idea that Harvey's acts were somehow the result of projecting his own depression onto his patients (although he also sometimes rejects this explanation).

While Whalen attempts to set Harvey apart by comparing him against a description from a book that stereotypes serial killers, he fails to make comparisons against studies of healthcare serial killers, aside from a passing glance at Charles Cullen (whom Harvey believes may have actually corresponded with him for a short time). Despite himself, Whalen makes it clear that like many serial killers, Harvey was cold-blooded about this business but was a complete coward when it came to his own death. He also loves attention, inflating his victim count to 87 when he was not getting enough, and he appears to be a callous narcissist. In other words, among serial killers, he's not that unique.

But there's a more important issue at stake. It's clear that Harvey should never have gotten the jobs he did, and since Cullen's story is sadly similar, we can see from this account that not much has changed since 1987 when Harvey was caught. Indeed, hospital administrations still protect their institutions and letters of warning to others still fail to get sent. In addition, the idea of an "internal investigation" by administrators who ignore whistleblowers is as much an empty gesture today as it was back then.

Yet Harvey offers a solution. He likes to "help" by describing his methods and telling hospitals what they did wrong in creating situations that allowed him to kill unhampered. In other words, he revels in his acts, blames others, and deflects responsibility from himself. So what else is new? There will always be ways for determined predators to kill, no matter what safeguards are put into place. The bottom line is, short of psychosis, they choose to exploit the trust engendered in healthcare communities and to take the lives of vulnerable people. There's not much here about Harvey to feel sympathy for.